Resources for Journalists

The GPCAH has assembled resources to help journalists cover stories related to Agricultural Safety and Health.

Instead of meeting live, we have assembled resources to provide journalists with information to help them in real time improve how they tell stories that can bring attention to hazards and provide best-practice guidance. Key information provided in this 2025 virtual workshop include:

-

- Updates on injury rates and trends, including a way to navigate through public databases on worker injuries, illnesses, and fatalities.

- Tips on terminology to help farmers reflect on their own hazards and safety

- One-page descriptions of resources available by story type (hearing protection guidance; gas monitors for manure pit/grain bin entry; respiratory protection fit testing tools)

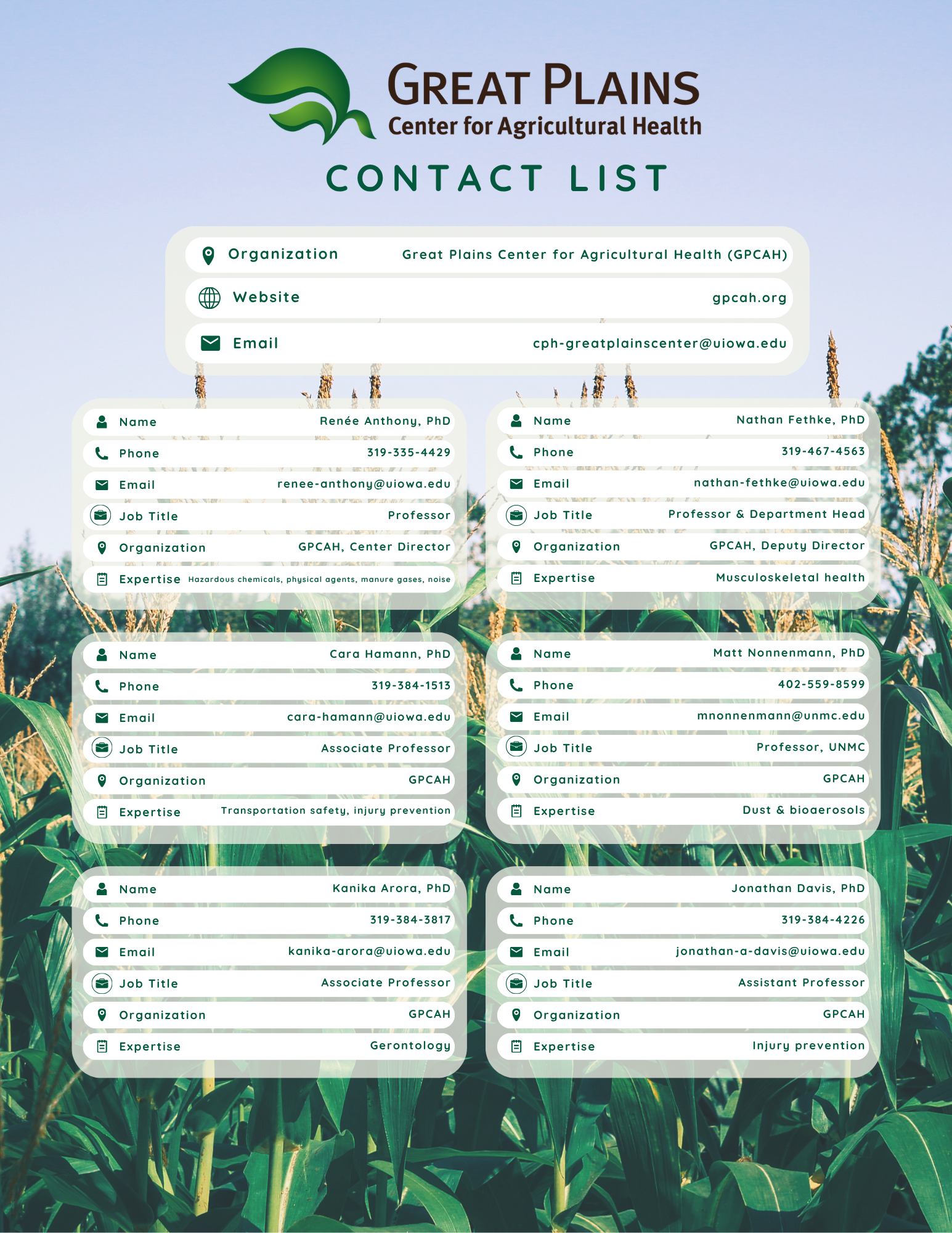

- List of subject matter experts available to discuss agricultural safety and health

- Links to additional resources on a wide variety of agricultural safety and health topics

Introduction

Rich Gassman, Director of ICASH, and Renee Anthony, Director of the GPCAH, want to thank you for visiting this page and learning important information to help share stories about hazards and injury prevention on the farm.

Journalists play an important role in bringing attention to on farm risks, helping all of us understand what is hurting people across our farming community. Our Midwest farmers have trusted journalists to tell their stories, and we believe that the media can help build a community to help influence safer behaviors and that these stories can help farmers understand their susceptibility to being injured from similar hazards on their farm. Stories that include best practices –those that share solutions to avoid injuries — help our farming community move toward safer and healthier operations.

Information below is provided to help journalists identify resources and understand more about this industry. These tips are based on common questions that we receive from journalists, to help you navigate resources on important topics. We hope that these tools help you to tell the story about important agricultural incidents in the media while sharing information on how to prevent similar events in the future.

Staff and researchers at both ICASH and the GPCAH are able to help answer technical questions you might have, and we have resources for who to contact about different stories, below.

And, as always, thank you for your interest in protecting one of America’s most important resources – our Farmers.

Trends on Agricultural Injuries

Recent injury data include:

- In the US, an average of 154 ag workers die per year from fatal injuries, averaged over the past 10 years (link)

- In the past few years, an average of 10,510 farmer injuries per year resulted in farmers not being able to go back to work, and 1/3 of these happened because of a fall (link)

- In Iowa, using 2017-23 Iowa Trauma Registry data (emergency room visits), the following preliminary trends have been identified (final analysis is found here):

- Around 500 Ag Injuries are reported each year,

- 2% of all people with traumatic injuries who are taken to the emergency room are from farming injuries,

- 64% of traumatic injuries on the farm happen to those older than 45 years,

- Twice as many farmers aged 55 years and older go to the ER because of a fall compared to younger farmers, and

- 26% of injuries are from falls, 23% from transportation, and 29% from being struck by or contacting dangerous machinery.

Finding Injury Data on BLS

In the US, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) compiles information used to report worker injury and illness. It tracks both fatal outcomes in the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) and non-fatal injury and illnesses (IIR). Every November-December, annual reports come out for both fatal and non-fatal cases, usually for the year ending 2 years prior.

We have prepared a 30-minute video that will walk you through how to find and use data in the BLS to understand both national and state data on injury and fatality surveillance at US workplaces.

As you use these databases, remember these definitions about important terminology:

- “Cases” are simply counts of workers who were injured/become ill during this 12-month calendar period

- “Rates” are calculated so that the number given is a “case per 100 full time equivalent workers”

- If the rate is “4.2 injuries” that means “4.2 injuries per 100 full time workers in that year”, where a full-time worker is defined as 40 hours/week, 50 weeks per year, thus a full-time equivalent worker is presumed to work 2000 hours per year (50 weeks with 2 weeks off).

- Rates are calculated so that we can compare rates of injuries between facilities or between industry sectors (NAICS codes in the BLS data) regardless of how many workers there are (and how many total hours worked per worksite).

For 2023 data, using table SNR05, we can see that for the Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (AgFF) industry (NAICS=11):

- The “Incidence rate” of injuries was 4.0

- The “Number of cases” was 38,200.

This means that 38,200 AgFF workers were injured to the extent that it needed to be recorded (beyond first aid) in the 12-month period (2023). The 4.0 is to be read that: there are 4 recordable injuries for every 100 full-time equivalent workers in AgFF.

Let’s compare to construction workers (NAICS 23) over the same time:

- The “Incidence rate” was 2.2,

- The “Number of cases” was 167,600

We see that there were MANY MORE cases in construction compared to AgFF. But, because there are a lot more workers in the construction sector, the incidence rate is lower: 2.2 recordable injuries per 100 full-time equivalent workers in construction.

This is why it is important to know what these numbers mean: More construction workers are injured by count, but a higher proportion of farmers are injured on the job than construction workers, which we can see in the rate.

Terminology Is Important

We are asking for journalists for two considerations when addressing injuries. This is true of agricultural workers as well as those at other workplaces, and using more specific descriptions will make your stories more impactful to the reader.

Accident vs Incident/Event

The first is our request to minimize the use of “accident” when reporting a story or making a headline to, instead, focus on the event or outcome.

The field of safety has moved from “accident” from its vocabulary because it implies that there is no fault, guilt, or control over the outcome. We know that this simply is not the case in many on-farm injuries, and using descriptions that convey what happened are more appropriate. For example, in 1997, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) officially changed its terminology from “motor vehicle accidents” to “motor vehicle crashes” (link).

Marshfield Children’s Center explains the issue in detail in a commentary, focusing on reporting children’s injuries on the farm, explaining that “to influence behavioral changes that increase safeguards for children in young workers in agricultural settings, using terminology aligned with the actual events is better to prevent others from enduring the same outcome.”

Identifying the Event and the Injury help explain what happened better than using “accident”. For example, if the event is a crash (e.g., between a pickup and a tractor or between an ATV and a car) or if the event is a tractor rollover, the outcome may be that someone is fatally injured or is seriously injured (and maybe someone was thrown from the vehicle). These types of descriptors are more specific than “tractor accident” that then helps other farmers see the specific hazards on their own farm.

Killed vs Fatally Injured

Another subtlety is the use of “killed” versus “fatally injured”. Killing implies a different intention and causality, and it focuses on the death and not on what happened. When we use “fatally injured”, we change the conversation to what happened (the events leading up to the injury), which again triggers readers to start thinking of events that could happen on their farm that could lead to this same outcome.

We have produced a 13-minute FarmSafe podcast (Season 4, Episode 2) that discusses these issues with the authors of the Marshfield Children’s Center commentary, and this page also contains links to additional resources.

Journalist Resource One-Pagers

For our live workshop, we prepare demonstrations of equipment to help journalists handle important equipment that they might want to ask about during a story. We have also developed one-page synopses about the equipment, but more importantly have identified:

- What type of stories would make you think about this resource?

- What is the risk to Ag workers?

- Recent news stories related to the topic

- Recommendations on approach discussions about the equipment when working on a story

- What you need to know to protect yourself from that hazard when you are on the farm

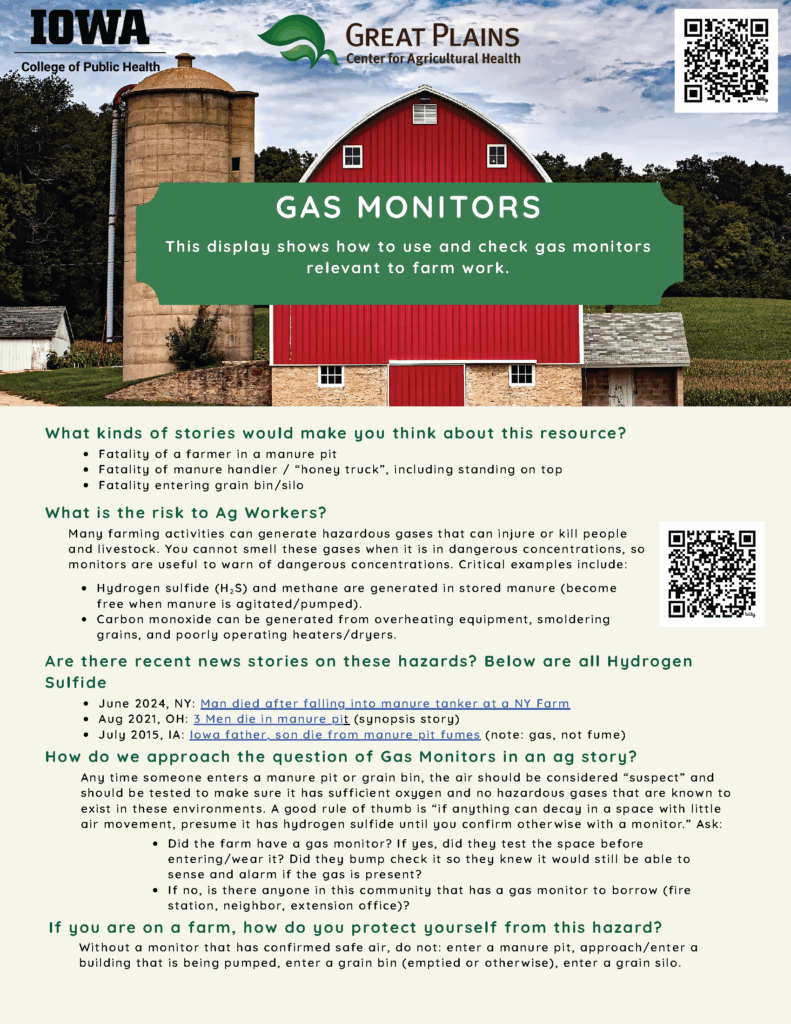

Gas Monitors

For manure handling and grain bin entry

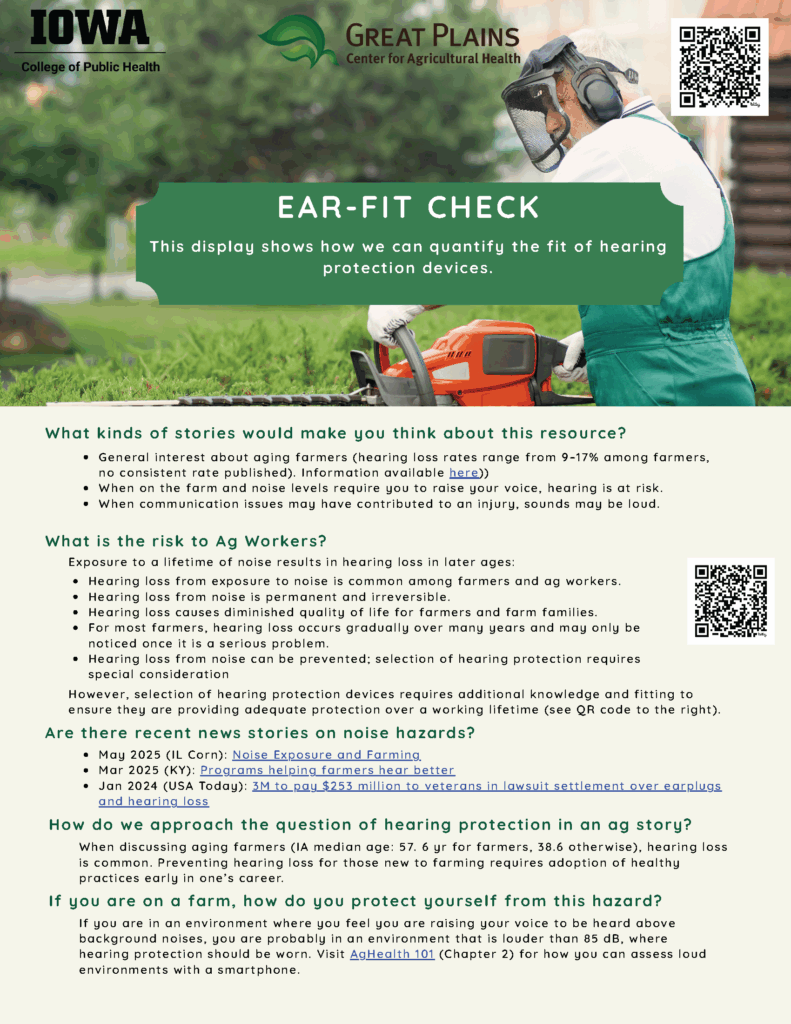

Ear-fit-Check

When you encounter loud sounds on a farm, this one-pager provides information on testing goodness of fit for hearing protection

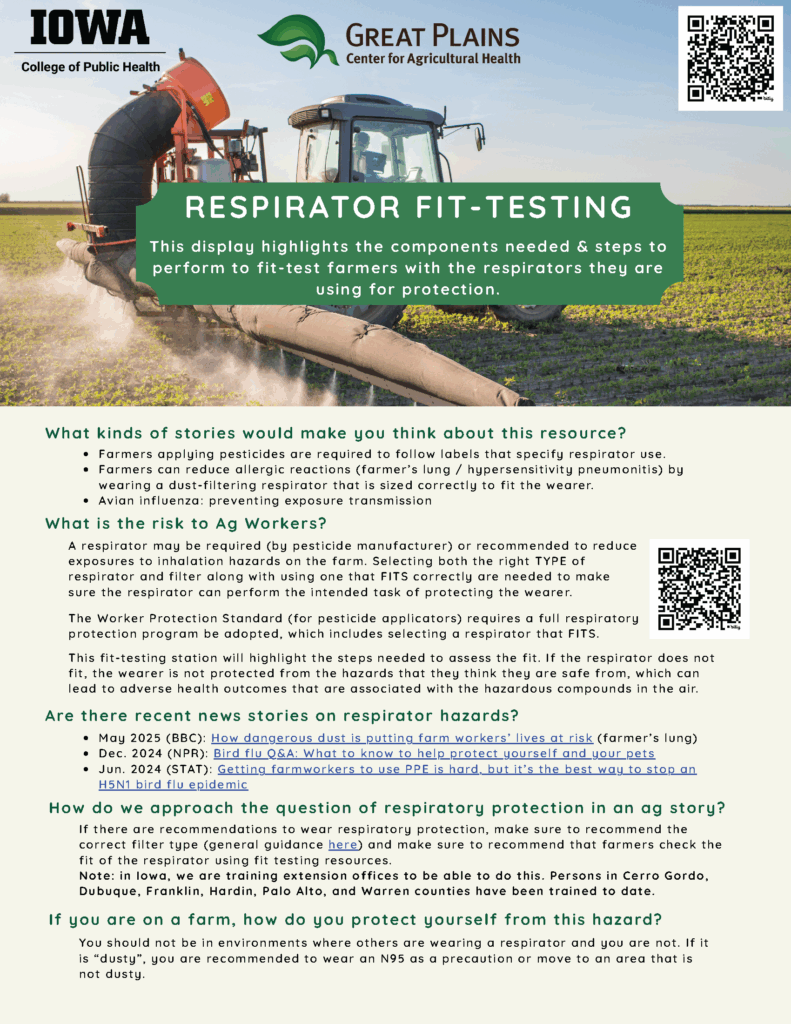

Respirator Fit-Testing

When farmers use respirators on the farm (e.g., for pesticide handling/application, to minimize allergic reactions to organic dusts, or when responding to zoonotic diseases)

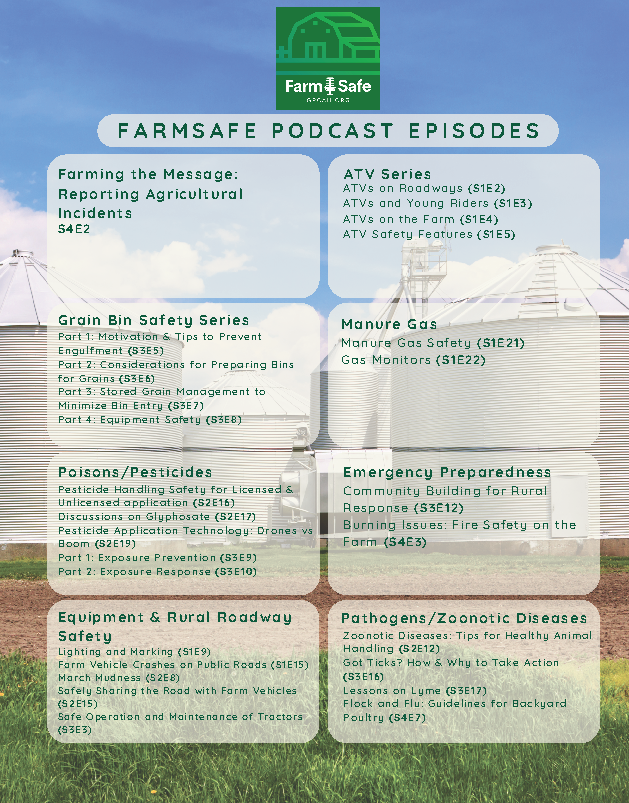

FarmSafe Podcast Episode Guide

A one-pager that contains information on episodes that are related to stories you might be working on (organized by topic)

List of University of Iowa Ag Safety and Health Experts

Attached is a downloadable document identifying persons and their areas of expertise should you be working on a story. Our web site includes brief information on key personnel associated with our center, but the pdf below contains additional experts at the University who are working on additional areas relevant to protecting the safety and health of farmers and farm workers.